It’s long been a fascinating journey optimizing CKB-VM. For example, here’s the runtime gathered when running secp256k1 verification on CKB-VM:

| | µs | Ratio |

|-------------------------------|-------|--------|

| CKB-VM (Rust interpreter) | 12034 | 316.68 |

| CKB-VM (Assembly interpreter) | 2417 | 63.61 |

| CKB-VM (Old AOT) | 1741 | 45.82 |

| Wasmtime 0.40.1 | 228 | 6.0 |

| WAVM nightly/2022-05-14 | 185 | 4.87 |

| Native | 38 | 1.0 |

For wasm tests, we compile the same secp256k1 test program above using WASI_SDK 16.

CKB now uses the assembly interpreter in production, which takes roughly 63 times the runtime of the native version to run the same code.

While the number above is good enough for its initial use case, the optimization work does not stop here. In an experimental branch, CKB-VM, with RISC-V V extension enabled, can achieve the following benchmark results performing alt_bn128 pairing check used in ethereum.

| test | CKB-VM (ns) | Native (ns) | Slowdown Ratio |

|-------------------|--------------|-------------|----------------|

| jeff1 | 22849143 | 2201627 | 10.37829887 |

| jeff2 | 22821825 | 2370538 | 9.627276593 |

| jeff3 | 22908230 | 2099845 | 10.90948618 |

| jeff4 | 29457042 | 2936476 | 10.0314261 |

| jeff5 | 29446342 | 2854710 | 10.31500292 |

| jeff6 | 22965152 | 2231241 | 10.29254661 |

| empty_data | 9380158 | 750076 | 12.5056101 |

| one_point | 16386542 | 1491860 | 10.98396766 |

| two_point_match_2 | 22520464 | 2077081 | 10.84236195 |

| two_point_match_3 | 22933197 | 2109833 | 10.86967405 |

| two_point_match_4 | 22907839 | 2095003 | 10.9345137 |

| ten_point_match_1 | 74829613 | 8210023 | 9.114421848 |

| ten_point_match_2 | 75258830 | 8331438 | 9.033114091 |

| ten_point_match_3 | 23011676 | 2155727 | 10.67467077 |

Note that the 2 tables shown above uses different time metric: the previous one is measured in microseconds, while the latter one is in nanoseconds.

This means with the help of V extension, CKB-VM can run the same algorithm within an order of magnitude compared to native code. And let’s not forget that CKB-VM tested here is still a simple interpreter design, which personally I think is already quite a decent result.

And we can go even further than this:

$ git clone https://github.com/xxuejie/ckb-vm-bench-scripts

$ cd ckb-vm-bench-scripts

$ git checkout 1a3d3c7141ba96674d655269bb61e76100508a4d

$ git submodule update --init --recursive

$ sudo docker run --rm -it -v `pwd`:/code nervos/ckb-riscv-gnu-toolchain:bionic-20211214 bash

root@27cec412ae10:/# cd /code

root@27cec412ae10:/code# make

root@27cec412ae10:/code# exit

$ cargo install --example ckb-vm-llvm-aoter \

--features llvm-aot ckb-vm-contrib@0.2.0

$ ckb-vm-llvm-aoter -i ./build/secp256k1_bench_10000 --generate run-result -t run 033f8cf9c4d51a33206a6c1c6b27d2cc5129daa19dbd1fc148d395284f6b26411f 304402203679d909f43f073c7c1dcf8468a485090589079ee834e6eed92fea9b09b06a2402201e46f1075afa18f306715e7db87493e7b7e779569aa13c64ab3d09980b3560a3 foo bar

Time to generate object: 1.686690072s

Time to run program: 886.551225ms

In the above section, we do the following things:

- Build the same code to do secp256k1 verification as used in the first benchmark, but tweak the code to run 10000 times

- Install a binary to run RISC-V programs via CKB-VM’s new LLVM based AOT engine

- Use the LLVM AOT engine to run the secp256k1 verification code

Log shows that it takes about 886.55 milliseconds to do 10000 secp256k1 verifications. If we do the math, this means the new LLVM AOT engine can do 1 secp256k1 verification in 88.655 microseconds, Which is merely 2.34x of native speed! Now we can complete the benchmark:

| | µs | Ratio |

|-------------------------------|-------|--------|

| CKB-VM (Rust interpreter) | 12034 | 316.68 |

| CKB-VM (Assembly interpreter) | 2417 | 63.61 |

| CKB-VM (Old AOT) | 1741 | 45.82 |

| Wasmtime 0.40.1 | 228 | 6.0 |

| WAVM nightly/2022-05-14 | 185 | 4.87 |

| CKB-VM (LLVM AOT engine) | 89 | 2.34 |

| Native | 38 | 1.0 |

This is even more interesting when we focus on all the variations of CKB-VM:

- Assembly interpreter runs plain RV64IMC code in 63x the runtime of native x64 programs compiled from the same code.

- Old AOT(to distinguish between the two, I will refer the previous AOT engine powered by dynasm as

old AOT, and the new AOT engine powered by LLVM asLLVM AOT) engine runs plain RV64IMC code in 45x the runtime of native x64 programs compiled from the same code. - By vectorizing code using RISC-V V extension, CKB-VM runs V enabled code in 10x the runtime of native x64 programs for the same algorithm.

- New LLVM AOT engine runs plain RV64IMC code in 2.34x the runtime of native x64 programs compiled from the same code.

I’m sure you will wonder how this is achieved, this post will talk in more details about the new LLVM AOT engine, including its design and unfinished work for the future.

Warning: this is gonna be a loooooooooong article. I do want to keep everything together as a reference(a good excuse for being lazy :P), but feel free to jump to individual sections as you like:

Design

The design for the LLVM AOT engine, keeps coming back to one question: what are the differences between code executed via CKB-VM, and code executed natively on a x64 machine? Like all virtual machines, CKB-VM will naturally incur many overheads on the program running inside, but what overheads can be removed, and where is the absolute upper limit we can aim?

JIT/AOT

First thing here is the interpreter overhead of course. All interpreters, no matter how fast they are, will contain decoding & cleanup work, which are useless to the actual computation but still consumes time. I touched this on a previous presentation, note please do ignore the benchmark numbers included in the slides, they are done in a defected way, while the numbers include in this post are more recent, and are to the best of my knowledge, performed in a more precise way.

To aim at the absolute limit, we will have to compile RISC-V assemblies to native assemblies for the host platform somehow. The old AOT engine uses dynasm for this task. Looking back now, I wouldn’t really say that the old AOT engine is compiling the code, it’s more like transpiling each RISC-V instruction one by one into a few assemblies for the native platform. This actually makes sense, since dynasm really stands for dynamic assembler. Even in LuaJIT, the original use case for dynasm, it’s only the interpreter that is built via dynasm, the underlying JIT uses a different code emitting solution with a whole lot of optimizations sitting on top. In a nutshell, the old AOT engine is merely assembling code, not compiling code.

I don’t have the time to build a full compiler with a lot of moving parts, nor do I think I can compete with some of the best minds in our industry. That brings me to a common solution: LLVM will be leveraged here as the workhorse to compile RISC-V assemblies to native code. Here’s one funny story to support the above argument: while working on the LLVM AOT engine, I used this program as a simple test to build the LLVM glue part, and LLVM took the liberty of optimizing this whole program to the following native code:

0000000000000000 <function_10078>:

0: 49 c7 44 24 38 01 00 movq $0x1,0x38(%r12)

7: 00 00

9: 41 c6 84 24 21 01 00 movb $0x2,0x121(%r12)

10: 00 02

12: bb 9c 01 01 00 mov $0x1019c,%ebx

17: ba 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edx

1c: b9 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%ecx

21: 41 ba 5d 00 00 00 mov $0x5d,%r10d

27: 31 f6 xor %esi,%esi

29: e8 00 00 00 00 call 2e <function_10078+0x2e>

(Please ignore the final call here, the call here really uses FFI to call into Rust code denoting CKB-VM to exit execution)

All the tests, branches in the original RISC-V program are optimized away, LLVM has executed those branches internally in the optimization passes, leaving only a few x64 instructions to set the RISC-V registers to final values when exiting the program.

This serves as an illustration as the distinction between compiling and transpiling/assembling mentioned above. The old AOT engine won’t perform optimizations like this. Nor am I saying all programs running on the LLVM AOT engine will be optimized away, but it’s one step closer to the upper limit.

You might also notice that I keep using the phrase AOT instead of JIT. I personally consider a JIT would have the following workflow:

- An interpreter powers initial execution, and profiles either function calls(method JIT) or control flows(tracing JIT) at runtime.

- Only when a piece of code becomes too hot, does the JIT optimizes the code, resulting in native code to be executed later.

Both AOT engines implemented for CKB-VM would compile the whole program ahead of time without running it first, resulting a whole pile of native code somewhere, only at this point does the VM boot with the native code installed. No profiling work is performed by CKB-VM in both AOT engines. Hence we are calling it AOT, not JIT.

That being said, there is still difference between the 2 AOT engines: the old AOT engine generates a bulk of binary data, all one needs to do, is marking the binary data as executable in memory, and the old AOT engine is good for execution. One can even save the binary data locally to a plain file, then load it back to memory later for execution. The LLVM AOT engine, on the other hand, would generate object file, one either statically links the object file with his/her program, or further build a dynamic linking library from the object file, then loads it dynamcally via dlopen at runtime. Either way, the LLVM AOT engine is more leaning into the build process, than a runtime component.

AST Preprocessor

Luckily, the AST data structure used in the old AOT engine is still usable. While a direct documentation on the AST is not available, an AST interpreter function combined with trait implementations on u64 type provides a reference implementation on AST semantics. Like the old AOT module, an AstMachine is built so we can execute RISC-V instructions on the AstMachine, reducing RISC-V instruction semantics to simplified register & memory writes using simple AST values, much like the example below:

Basic block (insts: 9) 0x101bc-0x101d6:

Possible targets after block: 0x1a4d4, 0x101d6

Write batch 0

Register[ a5 ] = 0x20

Write batch 1

Memory[ (Reg(sp) + 0x178) ]@4 = Reg(a5)

Write batch 2

Register[ a5 ] = 0x11

Write batch 3

Register[ a5 ] = (Reg(a5) << 0x23)

Write batch 4

Register[ a2 ] = 0x20

Write batch 5

Register[ a1 ] = (Reg(sp) + 0x8)

Write batch 6

Register[ a0 ] = (Reg(sp) + 0xa8)

Write batch 7

Memory[ (Reg(sp) + 0x170) ]@8 = Reg(a5)

Call to 0x1a4d4 (with writes) (sha3_update)

Register[ ra ] = 0x101d6

Which corresponds to the following original RISC-V instructions:

101bc: 02000793 li a5,32

101c0: 16f12c23 sw a5,376(sp)

101c4: 47c5 li a5,17

101c6: 178e slli a5,a5,0x23

101c8: 02000613 li a2,32

101cc: 002c addi a1,sp,8

101ce: 1128 addi a0,sp,168

101d0: fabe sd a5,368(sp)

101d2: 3020a0ef jal ra,1a4d4 <sha3_update>

101d6: 112c addi a1,sp,168

From there, we can focus only on the AST semantics when we build the LLVM based code generation engine, no RISC-V semantics are required here.

The preprocessor wraps this process with a few more things to work on:

- Use symbol table(if present) & inferred information(e.g:

jalwould mark the start of a function) to deduce all functions within an ELF object. - For each function, locate all basic blocks(a sequence of instructions that ends with a branch instruction) within the function.

- For each basic block, run the instructions included on the AstMachine, gather generated writes for each target(could be register or memory), the value in each write, will be in an AST value format. Notice a RISC-V instruction might generate more than one writes, they will need to be committed atomically.

- Each basic block, depending on the last instruction, could also generate a control change, based on RISC-V’s convention, some branching instructions will be interpreted specially, such as calls, returns, etc.

- The preprocessor also does limited AST simplification so as to simplify control changes.

After the preprocess function, we will have a set of functions consisting of basic blocks, each basic block will also contain a series of writes and control changes. Those shall be directly fed into the LLVM engine for actual code generation.

If you have followed the previous steps to run the LLVM AOT engine, you can use the following command to take a peek at the output from the preprocess function:

$ ckb-vm-llvm-aoter -i ./build/secp256k1_bench --generate writes

Register Allocation

Aiming at the upper limit, register allocation will be a huge topic. RISC-V has 32 general purpose registers with one additional PC register, while x64 only grants us 16 general purpose registers, one of them (rsp) has to keep the native stack. In the interpreter design of CKB-VM, all RISC-V registers are kept in memory. Even though the old AOT engine tries to tackle this problem, only ra, sp and a0 are kept in x64 registers. Others will be used for bookkeeping reasons, including 5 temporary registers due to a lack of register allocator! While I do believe the memory used to keep RISC-V registers will most likely be in CPU cache, still it prevents the CPU from doing renaming for better performance, unless running on very recent CPU. Even so, there are quirks we might run into, chances are the performance is still not on par.

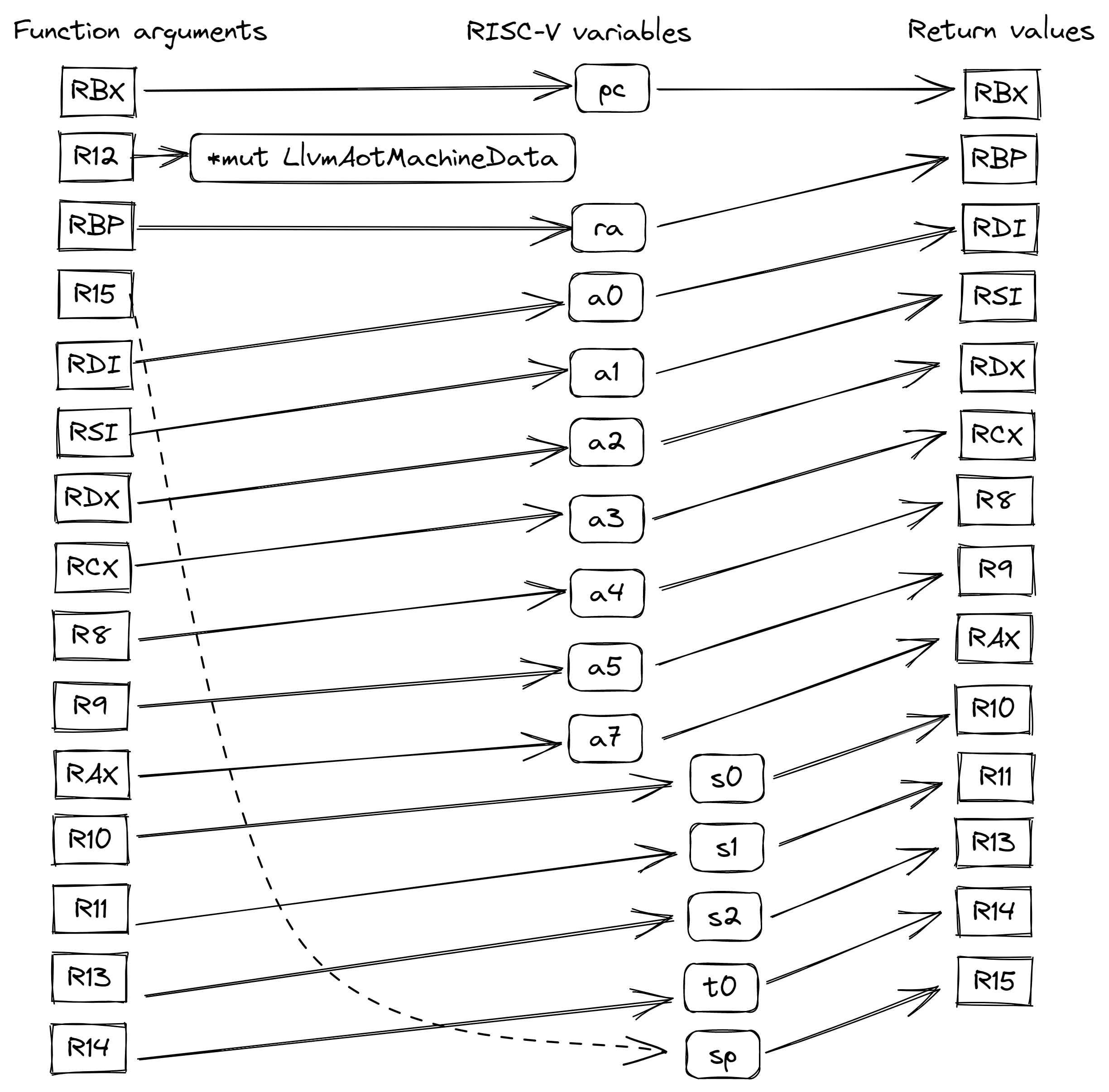

Drawing inspirations from the acedemia, HHVM calling convention can be used for this problem. First used by HHVM JIT, this special calling convention allows a function to have 15 arguments all put in registers, and also return 14 arguments in registers. In LLVM AOT engine, we design the code so each RISC-V function is generated into one native x64 function. Except for one argument used to keep a pointer to the LlvmAotMachineData struct, 14 x64 registers can be used to keep 14 hot RISC-V registers, and when the function returns, the updated values for those 14 RISC-V registers can also be returned as function arguments, to the caller function. This way we can keep as many RISC-V registers in x64 registers as possible. When temporary registers are needed(e.g: the unfortunate restriction that shift operands can only live in rcx, or that mul/div only affects rax/rdx), we can trust LLVM to help us perform correct register spills. This results in the following workflow:

- When booting the AOT engine, a function in x86_64 calling convention will load 14 RISC-V registers from the

LlvmAotMachineDatastruct, it then invokes the RISC-V entry function in HHVM calling convention using all 14 RISC-V registers together with a pointer to theLlvmAotMachineDatastruct. - When the RISC-V entry function is calling another RISC-V function in HHVM calling convention, it also passes the exact 14 RISC-V registers with a pointer to

LlvmAotMachineDatastruct.* A RISC-V function might choose to do certain operations among its RISC-V registers, for the 14 hot registers, they can simply alter the corresponding x64 registers, for the other RISC-V registers, memory load/store will be required with the help of pointer toLlvmAotMachineDatastruct. - When a RISC-V function returns, it would return the updated values for the 14 hot RISC-V registers.

- This process might continue for a bit.

- When we are finally ready to return to the x86_64 calling convention world from RISC-V functions, we use the latest values in the 14 x64 registers to update corresponding locations in

LlvmAotMachineDatastruct, writing back updated values.

Fundamentally, we are still storing all RISC-V registers in LlvmAotMachineData struct resided in memory, for a majority of computation, only the x64 registers are required. What’s left is just keeping the code within RISC-V functions using HHVM calling convention long enough.

There is still one quirk: due to some reasons, the order of registers used in function arguments, are different from arguments used in return values. For example, the 3rd argument is kept in rbp, while the 3rd return value is returned in rdi. If we simply denote the 3rd argument and the 3rd return value for one RISC-V register, for example, a0, there will still be operations moving values from rbp to rdi when a RISC-V function returns. While a simple register move is quite small, it is still work and could accumulate to be quite some running time. To avoid this situation, LLVM AOT engine is designed to use the following mapping:

Here we can see the RISC-V register a0 is passed as the 5th argument, and returned as the 3rd return value. The x64 register rdi, happens to be used both as the 5th argument and the 3rd return value in this design. As a result of this, no additional work will be needed to move registers around when returning from a RISC-V function.

Of all the 33 RISC-V registers, we can only keep 14 registers in x64 registers. This means we will have to prioritize hot registers. So while the actual RISC-V registers used in the above mapping might change in the future, the general mapping structure stays the same: for each hot RISC-V register, the same x64 register will be used to pass it both as function argument, and as return value.

HHVM set aside one callee saved register R12 for thread-local area, which can perfectly be used for us to pass the pointer to LlvmAotMachineData struct around. This pointer is only needed as an argument, all RISC-V function has it, so there’s no need to pass it as a return value.

With this design, I think we’ve achieved all we can in terms of register allocation, given the x86_64 architecture.

Mmap based memory

In all previous CKB-VM engines, memory boundary & permission checkings are manual performed in code. This solution, while being secure, completely ignores modern MMUs. The W^X policy used by CKB-VM now can perfectly be implemented via operating system constructs. Since the OS will check for this anyway, why bother performing the same checking in CKB-VM? The LLVM AOT engine runner is thus directly using mmap and similar constructs on non-POSIX OSes to initialize memory for CKB-VM, and thus relying OS to do memory permission checking. This new design does come with a few tradeoffs:

- Boundary checking becomes tricker since an attacker might try to trick the code on certain parts in current process, but do not belong to CKB-VM. This can be mitigate with several strategies:

- ASLR, or address space layout randomization is a widely used technique in modern OSes, meaning at each execution, our program can land on different addresses, hopefully rendering this technique to be less effective.

- Native Client also gives us an idea here: we can statically cap each address used for memory operations. For example, CKB-VM, in its conventional configuration, uses 4MB memory. This means for each address

addr,addr & 0x3fffffwill give the capped address well within valid address range. While this certain adds slightly more code to run, it shall be an acceptable compromise judging by the results from the Native Client paper.

- We will also need to consider error handling now: certain errors, such as memory violations, are not Rust errors anymore, they now become OS level signals. This means one might want to wrap the LLVM AOT engine in its own process for best security, and ease of handling.

- While the answer is not necessarily yes, there might be implications when we mark memory pages containing RISC-V instructions as executable on x64 machine. It requires more study to say if this will bring harm to the host machine.

There is also one thing that comes free: MAP_ANONYMOUS provides free, OS level zero-filled page, which means we don’t need to do manual memory initialization as well.

Calls

To best aid modern CPU’s branch predictors, LLVM AOT engine compiles each RISC-V function into each x86 host function. Each RISC-V function call is also transformed into an x86 host function call. This choice has implications on both sides:

On the good side, it simplifies the handling of returns. Take the following RISC-V function for example:

000000000001209c <secp256k1_pubkey_load>:

1209c: 711d addi sp,sp,-96

1209e: 87b2 mv a5,a2

120a0: e8a2 sd s0,80(sp)

120a2: e4a6 sd s1,72(sp)

120a4: 842e mv s0,a1

120a6: 04000613 li a2,64

120aa: 85be mv a1,a5

120ac: 84aa mv s1,a0

120ae: 850a mv a0,sp

120b0: e0ca sd s2,64(sp)

120b2: ec86 sd ra,88(sp)

120b4: 12c090ef jal ra,1b1e0 <memcpy>

120b8: 6722 ld a4,8(sp)

120ba: 66e2 ld a3,24(sp)

120bc: 6602 ld a2,0(sp)

...

There is a function call to memcpy at 0x120b4, calling into memcpy is a piece of cake, but what about returning from memcpy? There are 2 addresses involved:

- The RISC-V side return address

0x120b8 - The native x64 side address for executing

ld a4,8(sp)

Both the interpreter and the old AOT engine pay no attention to function calls at all, they all just treat calls as plain jumps, and only maintain the call stack at RISC-V side. Another way of seeing this, is that the old AOT engine treat an entire RISC-V program as a single function. Internally it’s jumps all the way down. While this certainly simplify things a bit, it confuses CPU’s branch predictor, which is one of the major bottleneck in current CKB-VM. To eliminate this overhead as much as possible, the LLVM AOT engine would maintain both stacks, and generate x64 native calls directly when RISC-V function calls are encountered.

Which brings us to the bad side of this design:

When the RISC-V call, emitted as a native x64 call is executed, 2 return values are generated:

- The native x64 return address is kept in x64’s stack

- The RISC-V return address is kept in RISC-V’s

RAregister, whether it’s kept in a x64 register or in memory

Here’s the return part from memcpy:

1b22c: 9be1 andi a5,a5,-8

1b22e: 07a1 addi a5,a5,8

1b230: 973e add a4,a4,a5

1b232: 95be add a1,a1,a5

1b234: 01176663 bltu a4,a7,1b240 <memcpy+0x60>

1b238: 8082 ret

At address 0x1b238, this function returns, different from x64 conventions, RISC-V expects the return address to be in RA register. A ret instruction is essentially just jalr zero, ra, 0.

Now there are 2 cases:

- For a program respecting RISC-V calling convention, when

secp256k1_pubkey_loadcallsmemcpy, by the timememcpyreturn,RAregister will contain the address insecp256k1_pubkey_loadfollowing thememcpycall, in the above example,0x120b8 - For a sophisticated(not necessarily evil) program that might be trying to be clever, it might modify

RAto be something else. At this stage, executingretwill not return us tosecp256k1_pubkey_load, but might take us to a different location in a different function. This means RISC-V calling stack does not always align with x64 calling stack. RISC-V specification allows such behavior to happen.

To cope with this situation, the LLVM AOT engine would generate code to save the value of RA register when executing a RISC-V call, and when later return happens, the generated code would check the value in RA register then, with the saved RA value. If they do match, the RISC-V calling stack does match the x64 calling stack, and we can use x64’s ret instruction to return to previous function. If not, maybe the program is trying to be clever, we will terminate the generated code from AOT engine, and resume executing via a CKB-VM interpreter mode.

This also introduce’s one design principle of the LLVM AOT engine:

CKB-VM’s LLVM AOT engine should be able to execute all programs permitted by RISC-V specification without errors. For certain programs that are predictable, the LLVM AOT engine should make them as fast as possible, closing to native speed.

ckb-vm-llvm-aoter is equipped with a fast mode switch. When turned on, it would only execute those programs that it can run fast, for programs that are valid but try to be clever, it might terminate with an error. When the fast mode is off, the LLVM AOT engine would perfectly run all RISC-V programs, it would switch to an embedded interpreter if AOT engine fails with certain code path.

Hurdling Special Code Path

Modern compilers are sophisticated enough that they would build all kinds of tricks to make program run fast. This means some program, while adhering the RISC-V specification as well as calling convention, might come as a surprise for us. We do want to make as many programs as possible to run fast on the LLVM AOT engine, this means sometimes we will have to cope with such successes. Here’s a story making unrolled memset to run fast.

The memset talked about lives at here, when compiled with GCC, the following code would be generated:

000000000001b2c8 <memset>:

...

1b2ee: 40c306b3 sub a3,t1,a2

1b2f2: 068a slli a3,a3,0x2

1b2f4: 00000297 auipc t0,0x0

1b2f8: 9696 add a3,a3,t0

1b2fa: 00a68067 jr 10(a3)

...

1b2fe: 00b70723 sb a1,14(a4)

1b302: 00b706a3 sb a1,13(a4)

// All sb operations here

1b332: 00b700a3 sb a1,1(a4)

1b336: 00b70023 sb a1,0(a4)

1b33a: 8082 ret

...

1b358: 00000297 auipc t0,0x0

1b35c: 9696 add a3,a3,t0

1b35e: 8286 mv t0,ra

1b360: fa2680e7 jalr -94(a3)

...

For the length of this already-super-long post, I’ve eliminated irrelavant part. Leaving 3 interesting pieces:

0x1b2ee-1b2fawould build a target PC value between0x1b2feand0x1b33a, and jump to it.0x1b2fe-0x1b33aall contains plainsbinstruction storing values at memory location0(a4)-14(a4).0x1b358-0x1b360would build a target PC value between0x1b2feand0x1b33a, treat it as a function entry point, and call to it.

If you look at the original C code, there’s no constructs like the above, this is actually due to loop unrolling, there is also a designated name for such a construct: Duff’s device. It helps remove the conditional branching needed to do at the expense of code size. I do want to warn you that Duff’s Device is not always a panacea, it can cause problems.

Basically, what we are dealing here, is 2 cases that are not previously handled by the LLVM AOT engine:

- The code jumps to a place that is not known as the start of a basic block.

- The code calls into a place that is not known as the start of a function, nor the start of a basic block.

Luckily, the 2 code pieces are not too long, and we can set some rules to handling them:

- When the code jumps to unknown place, call the interpreter to execute till the end of current basic block, then use current PC to find the next basic block. If we can find a basic block that starts with the same address as current PC, we navigate to this basic block and continue AOT mode execution. If not, we unwind to interpreter from now on.

- For each such function, we actually would generate a special code piece, that does binary searching on all basic block starts, finding the target basic block.

- When the code calls to unknown place, call the interpreter to execute till the end of function, then use current PC to find the next basic block. If we can find a basic block that starts with the same address as current PC, we navigate to this basic block and continue AOT mode execution. If not, we unwind to interpreter from now on.

- For now, we only handle the case that the inner function called is within current function. Internal calling into external function might be added later.

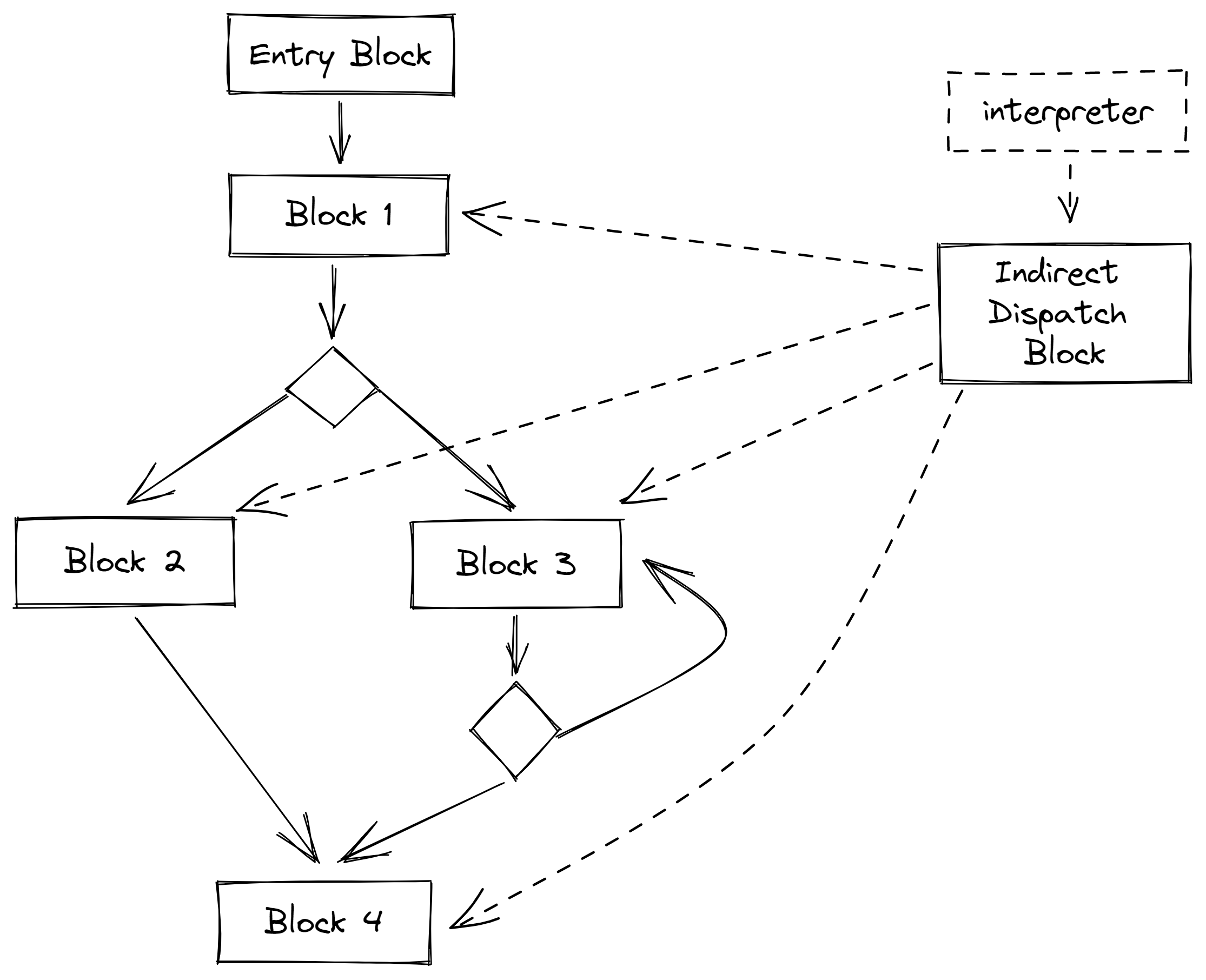

This means the actual control flow graph for a generated function, might look at the following: on the left there are block 1, 2, 3, 4 generated from the same constructs in the corresponding RISC-V function, on the right there is also an attached Indirect Dispatch Block, which does binary search and dispatch PC advanced by interpreter to either of the 4 blocks.

Some of you might have a question now: “previously you were saying that terminating AOT engine due to different calling stacks result in slow executiong in interpreter, but here you were also using the interpreter to get fast execution?”

The answer here, lies in the different terminologies:

- call the interpreter

- unwind the interpreter, or as in previous case, terminates the AOT engine

Call to interpret vs. Unwind to interpret

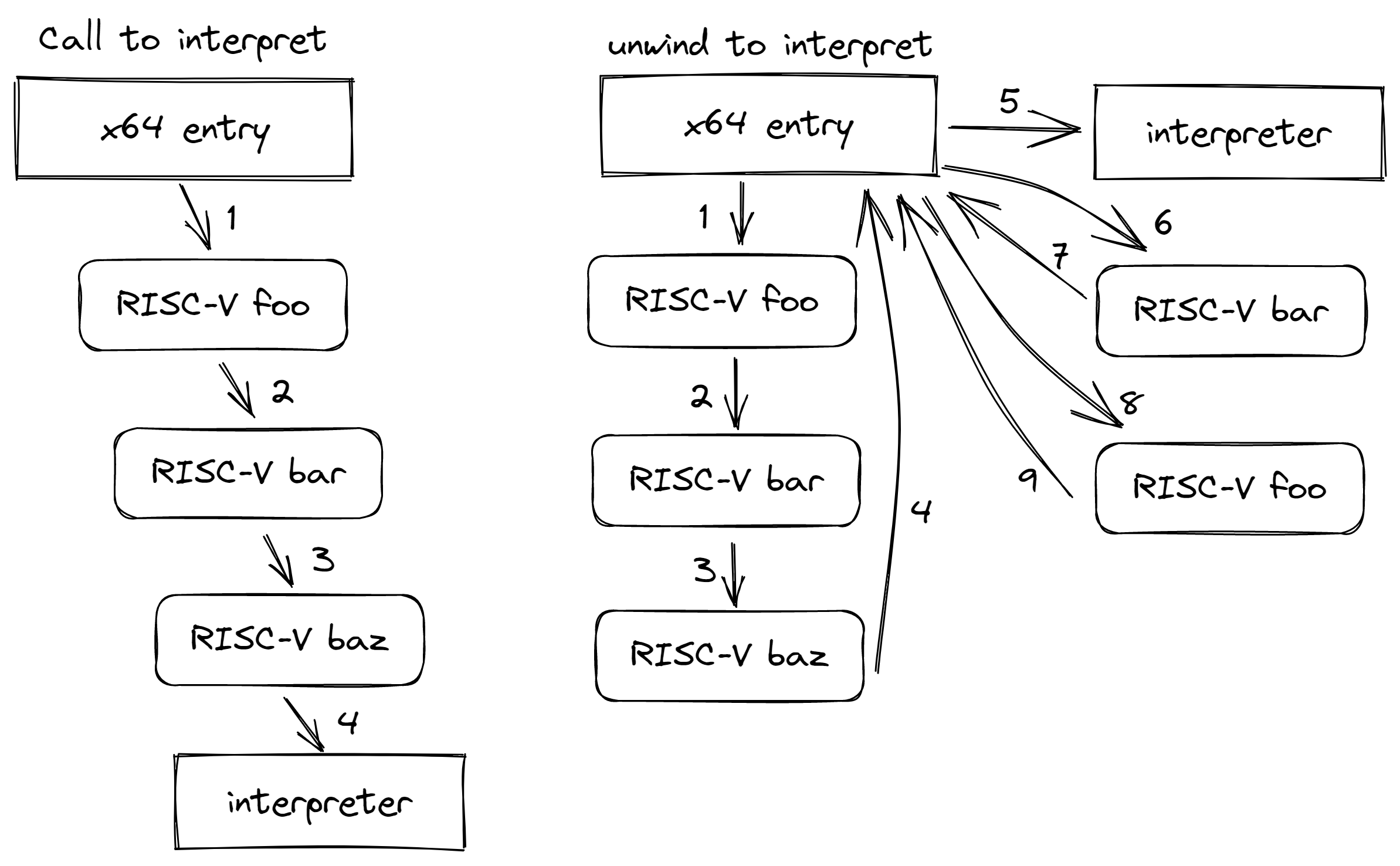

In the LLVM AOT engine, there are 2 ways to use the interpreter:

- A RISC-V function can call into the interpreter, asking the interpreter to interpret some code, the control is thus turned back into the RISC-V function, both calling stacks are not altered. This is shown as the graph on the left.

- The graph on the right, however, shows a different path: at some cases, such as a mismatched stack, the AOT engine cannot proceed further, as a result, we need to unwind the full x64 calling stack. In the above example, this means the x64 calling stack for

foo,barandbazare all destroying, reverting back to x64 entry function, which then calls into the interpreter to execute some code. Even later we decide that we might re-enterbar, there is only RISC-V calling stack forbarpreserved, the x64 calling stack forbaris completely discarded. This means when bar returns, there will not be matching x64 stack forfoo, once again the control will be unwinded to x64 entry function. This is the slow path we definitely want to avoid.

Recap

There might be more overheads hidden, we are still revising the design. But those changes already push CKB-VM way forward towards the absolute limit. We might never reach native speed due to the extra work such as setting extra PC, maintaining dual calling stack, return & indirect checkings, but we will be sure to aim at high as we can get.

Unfinished Work

There are also certain known work that can be done now.

More Host Architectures, More Guest Configurations

Right now the LLVM AOT engine is tied on running RV64IMCB code on x86_64 machine. But there are certainly other directions we can push forward:

- Run the LLVM AOT engine on aarch64 host machine.

- With VisionFive 2 coming, will it make sense to run CKB-VM on a true RISC-V CPU? And what are the challenges?

- Running other RISC-V configurations is also an interesteing choice, such as RV32IM or RV32IMF

LLVM Related Work

There are indeed more LLVM related work done the pipeline. The most imminent one IMHO, is debugger support. Embracing LLVM has one huge advantage here, in that a lot of tooling is already there provided by the awesome community, including DWARF support. We shall be able to attach the original RISC-V assembly code to the generated x64 code, hoping to find bugs easier as well as more points to optimize. As a further thinking exercise, what if we can attach the original Rust/C code before the RISC-V assembly, to the final generated x64 code?

Another thing we shall be looking at, is LLVM’s optimization passes, right now we got there by applying a few simple passes as recommended in the Kaleidoscope tutorial. But building a native code translator definitely employs different tradeoffs from building a high-level language compiler. It’s worthwhile going through LLVM passes to see if we can further squeeze some performance.

Lastly, there is also one exciting topic: LLVM has introduced ScalableVector in preparation for RISC-V V extension as well as ARM SVE. While one path is tapping LLVM AOT engine with the V extension interpreter, what if we can leverage LLVM ScalableVector to build RISC-V V extension support? Will that bring something totally different to the table? I gotta admit I wasn’t so familiar with LLVM ScalableVector, and I’m only dreaming here.

Inferring on memset constructs

As mentioned above, while all RISC-V programs run on the LLVM AOT engine, some are powered by interpreter. We do want to minimize those programs that require unwinding to the interpreter. I will definitely keep looking at different programs, trying to make as many of them runnable in the fast mode of LLVM AOT engine. A good starting point, is those programs generated by GCC/LLVM.

Conclusion

I still have some other topics I want to talk about but this is already a super long one. It probably is better to save for another day. In the meantime, the introduction on the LLVM AOT engine is rather complete. Let’s hope we can put it to good use :)